A “New Haven” for David Atwater …

David Atwater lived from 1615 to October 5, 1692

David Atwater’s ancestral home in Royton, Lenham, Kent, England was acquired during the early years of the reign of Henry VIII. Royton is mentioned in English records as early as 1259, when Simon Fitzadam was in possession of the manor of Royton. His successor was Robert de Royton, who took his surname from this place. The manor was purchased by Robert Atwater early in the reign of Henry VIII and it was in the possession of his descendants through his daughter for several centuries.

David was born in 1615 Royton, Lenham, Kent, England the son of John Atwater and Susan Narsin and came to North America June 26, 1637 when he was 22. He sailed to America on a ship named Hector. Traveling with him was John Davenport and Theophilus Eaton (founders of New Haven). Joshua and Ann his sister and brother where also aboard. See Wikipedia.org – David Atwater.

From Boston the group made their way to the Quinnipiack – (Quinnipiac) home of the Quinnipiack Indians. But they returned to Boston because of their lack of preparedness of the New England winter, David’s Brother and 7 others remained in New Haven. Returning in the spring of 1638 and settled there. On June 4, 1639 he signed the plantation covenant in Francis Newman‘s barn along with 20 others. The valuation of their land was £500 and up.

The immigration of David and his brother and sister is probably typical of those of Puritan sect. Their father, a warden of the church at Lenham, died within six months of his wife in the midst of the “eleven years tyranny’ of Charles I and the purging of Puritans from the Church of England by Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud. Ashford, which was named in letters to the King on several occasions by William Laud as a hotbed of Puritan activity, lies about nine miles from Lenham.

See Pilgrims v. Puritans: Who Landed in Plymouth? from The Historic Present Blog.

While Lenham is not mentioned specifically, it is evident that the children of John Atwater were infected by Puritanism, and with the death of their parents in 1636/7, it made sense for them to leave the country for the New World and a chance to practice their religion.

Lenham is a town and parish in Mid-Kent, between Maidstone and

Ashford, deriving it’s name from the river Len and Ham, which

signifies a town. The parish registers of St. Mary’s, the old church

of Lenham, record the baptisms of David, Joshua, and Ann, the baptism

of their father, their parents marriage, and their parents burials.

The wills of their ancestors stipulate burial in the churchyard of

Lenham church. Royton is a district in the parish of Lenham. The name applies to a section of the parish which had an organization of its own in ealry times, and a market regularly held within or near its limits. In 1901, in the year of the writing of Atwater’s History, Royton Manor was

somewhat of a tourist attraction in Kent.

In the record books of early New Haven David’s name occurrs

In the record books of early New Haven David’s name occurrs

frequently, although not as much as his distinguished brother. The

surviving map of the ‘Nine Squares’ of 1641 New Haven shows his

homelot in the northeast quadrant of New Haven. There is a difference of opinion in the history and genealogical books over exactly when David and his brother Joshua came to America. A Puritan minister named John Davenport led his flock from exile in the Netherlands back to England and finally to North America in the spring of 1637.

That fall, Theophilus Eaton led an exploration party south to the north shore of Long Island Sound in search of a suitable site. He purchased land from the Indians at the mouth of the Quinnipiac River. In the spring of 1638 the group set out, and on April 14 they arrived at their ‘New Haven’ on the Connecticut shore. The site seemed ideal for trade, with a good port lying between Boston and New Amsterdam which gave good access to the furs of the Connecticut River valley settlements of Hartford and Springfield. However, while the colony succeeded as a settlement and religious experiment, its future as a trade center was some years away.

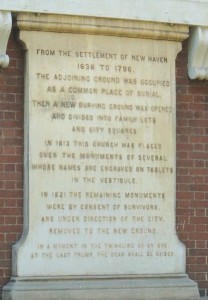

The family genealogy books assert that they came in 1637 and were on the ‘advance party’ to New Haven, commemorated 250 years later with a granite slab in New Haven that reads: ” “Six men, under the direction of Joshua Atwater, a merchant of Kent, England, encamped near this spot in the winter of 1637-8…” In any case, David and his brother were among the founders of this breakaway Puritan community that sought to form a true theocracy, believing that already the Puritans at Boston had swayed from their original intentions. The group arrived in Boston on the ship Hector on June 26, but decided to strike out on their own, thanks to their impression that the Massachusetts Bay Colony was lax in its religious observances.

That fall, Theophilus Eaton led an exploration party south to the north shore of Long Island Sound in search of a suitable site. He purchased land from the Indians at the mouth of the Quinnipiac River. In the spring of 1638 the group set out, and on April 14 they arrived at their ‘New Haven’ on the Connecticut shore. The site seemed ideal for trade, with a good port lying between Boston and New Amsterdam which gave good access to the furs of the Connecticut River valley settlements of Hartford and Springfield. However, while the colony succeeded as a settlement and religious experiment, its future as a trade center was some years away.

In 1639 the colonists adopted a set of Fundamental Articles for self-government, partly as a result of a similar action in the river towns. The articles required that “…the word of God shall be the only rule…” and this was maintained even over English common law tradition. Their law came from Deuteronomy and not English Common Law. Since the Bible contained no reference to trial by jury, they eliminated it, and the council sat in judgment. Only members of the church congregation were eligible to vote. See History of the Colony of New Haven and its absorption into Connecticut by Edward E. Atwater.

The Puritan migration was overwhelmingly a migration of families unlike other migrations to early America, which were composed largely of young unattached men. The literacy rate was high, and the intensity of devotional life, as recorded in the many surviving diaries, sermon notes, poems, and letters, was seldom to be matched in American life. The Puritans’ ecclesiastical order was as intolerant as the one they had fled. Yet as a loosely confederated collection of gathered churches, Puritanism contained within itself the seed of its own fragmentation.

Following hard upon the arrival in New England, dissident groups within the Puritan sect began to proliferate – Quakers, Antinomians, Baptists – fierce believers who carried the essential Puritan idea of the aloneness of each believer with an inscrutable God so far that even the ministry became an obstruction to faith.

The ensuing religious history of early New England is a tale of conflicts between congregational and synodical authority; between those who stressed the utter helplessness of the individual in the process of salvation and those who began to allow a place for human initiative; between those who believed that the Lord’s Supper was a sacrament reserved for the regenerate and those who believed that it could be a “converting ordinance”; and perhaps most divisively as time went on, between those who regarded baptism as a rite due only to the children of full communing church members and those who believed it could be safely extended to the children of “half-way” members – second -generation Puritans who had never stepped forward to make the profession of faith that the founders had required for entrance into the true church.

These sorts of disputes – which have a certain inevitability in any community where the quality of true faith is the only value worth disputing – make the history of American Puritanism seem a story of family strife and, ultimately, of disintegration.

But Puritanism as a basic attitude was remarkably durable and can hardly be overestimated as a formative element of early American life.

Among its intellectual contributions was a psychological empiricism that has rarely, if ever, been exceeded in categorical subtlety. It furnished Americans with a sense of history as a progressive drama under the direction of God,

Though “the New England Way” evolved into a relatively minor system of organizing religious experience within the broader American scene, itscentral themes recur in the related religious communities of Quakers, Baptists, Presbyterians, Methodists, and a whole range of evangelical Protestants. And in its bequest of intellectual and moral rigor to the New England mind, it established what was arguably the central strand of American cultural life. See Alan Heimert and Andrew Delbanco, eds., The Puritans in America (1985); Perry Miller, The New England Mind: The Seventeenth Century (1939) and The New England Mind: From Colony to Province (1953).

We welcome your comments and contributions of material are most welcome. You may post comments and additional information on the Atwater Genealogy Message Board. Thank you for visiting www.AtwaterGenealogy.com